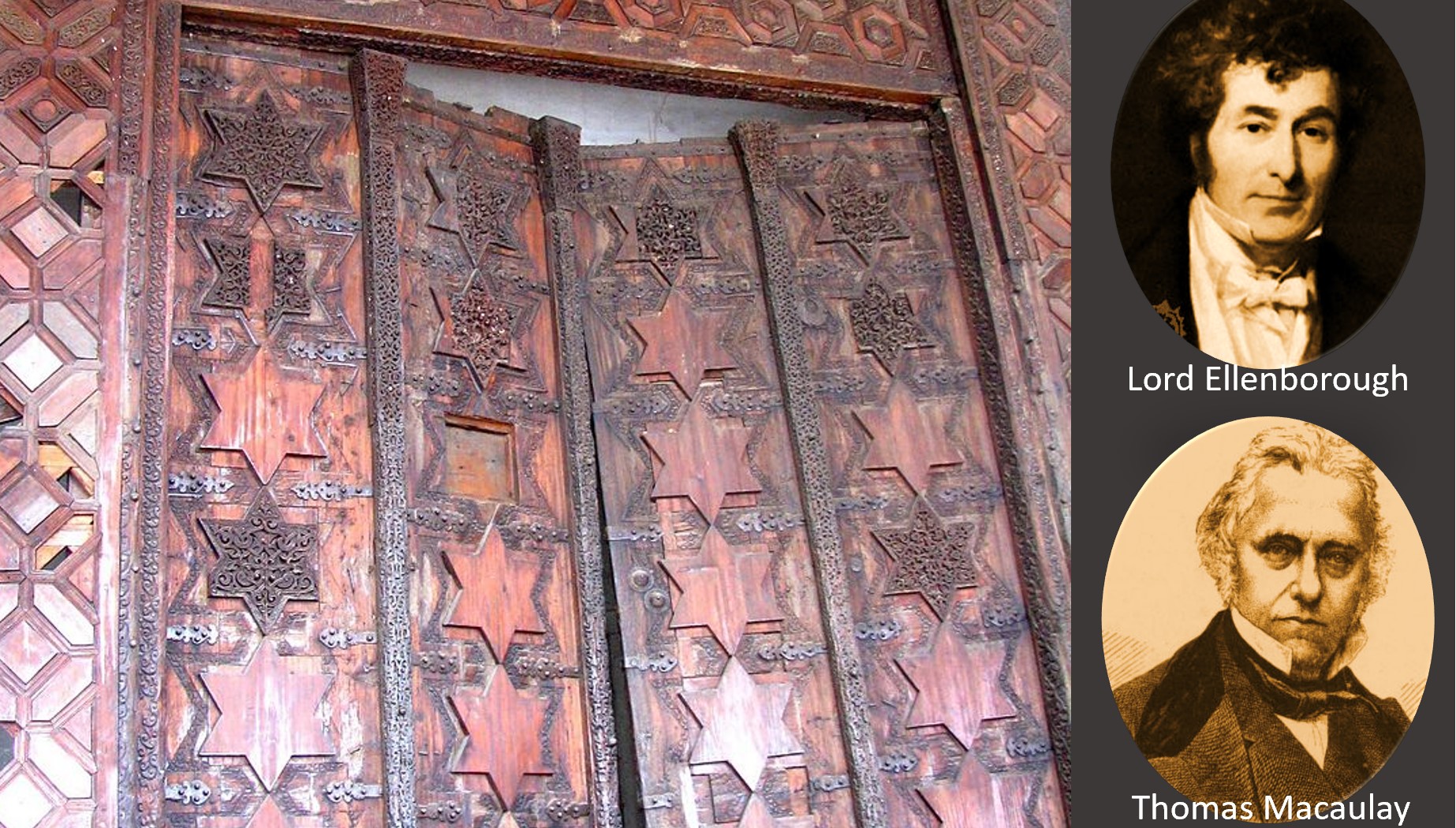

- The famous Somnath mandir gate was carried off to Afghanistan in 1026 CE by Mahmud of Ghazni as part of his plunders of India’s cultural riches.

- The gate was recovered and brought back to India by the British army after defeating the Afghan forces in 1842.

- Lord Ellenborough, then the Governor-General of India, was severely chastised for this “act of Hindoo appeasement.”

- Macaulay’s 1843 speech in the British Parliament, rebuking Ellenborough’s actions, exemplifies the prevailing Eurocentric attitude of the time, with a clear bias against Hindu traditions and a sense of Abrahamic kinship towards Islam.

The “Return of Somnath Gate” refers to a significant event in Indian history that took place in 1842 during the rule of Lord Ellenborough, the Governor-General of India, as part of the broader British colonization of the Indian subcontinent. This event involved the acquisition and eventual restoration of the Somnath Temple’s ancient gate, which held historical and religious significance for many Indians.

The Somnath Temple, located in the town of Prabhas Patan in the Indian state of Gujarat, is one of the most sacred Hindu temples dedicated to Lord Shiva. This temple has a long and storied history, having been rebuilt and renovated several times over the centuries due to various invasions and destructions.

In 1026 CE, Mahmud of Ghazni, a Muslim conqueror from Central Asia, attacked and plundered the Somnath Temple, taking away immense wealth and desecrating the temple. The wooden gates of the temple, adorned with precious metals and jewels, were also carried off as a symbol of victory and a sign of the temple’s conquest.

Fast forward to the 19th century, during the British colonial period in India. Lord Ellenborough, who was serving as the Governor-General of British-occupied India, sought to secure and strengthen British control over the Indian subcontinent. In 1842, Ellenborough’s forces launched an expedition to Afghanistan. During the course of this expedition, the British army encountered the gates of the Somnath Temple in the town of Ghazni, being used as a trophy or symbol of victory by the Afghan ruler, Shah Shuja. Colonel Cubbon, the commander of the British expedition, successfully negotiated with Shah Shuja for the return of the Somnath Gate to British possession.

The return of the Somnath Gate was a symbolic gesture by Lord Ellenborough to win the favor of the Indian population.

However, Ellenborough’s actions drew stiff criticism from the opposition members of the British Parliament. They accused him of using the return of the gate as a political maneuver to manipulate religious sentiments for political gain.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, the British parliament member better known for his role in molding British education policy in India via his “Minute on Education” in 1835, was particularly perturbed by Ellenborough’s actions. His speech of March 9, 1843[1] in the British House of Commons not only underscores his contempt for Indian society but also exemplifies the deep-seated prejudice held by British colonizers towards their Hindu subjects while showing sympathy for the sensitivities of the Muslim population.

We reproduce relevant paragraphs from Macaulay’s speech here:

“That this House, having regard to the high and important functions of the Governor General of India, the mixed character of the native population, and the recent measures of the Court of Directors for discontinuing any seeming sanction to idolatry in India, is of opinion that the conduct of Lord Ellenborough in issuing the General Orders of the sixteenth of November 1842, and in addressing the letter of the same date to all the chiefs, princes, and people of India, respecting the restoration of the gates of a temple to Somnauth, is unwise, indecorous, and reprehensible.”

We rule a multi-religious empire: “But the charge against Lord Ellenborough is that he has insulted the religion of his own country and the religion of millions of the Queen’s Asiatic subjects in order to pay honour to an idol. And this the right honourable gentleman the Secretary of the Board of Control calls a trivial charge. Sir, I think it a very grave charge. Her Majesty is the ruler of a larger heathen population than the world ever saw collected under the sceptre of a Christian sovereign since the days of the Emperor Theodosius. What the conduct of rulers in such circumstances ought to be is one of the most important moral questions, one of the most important political questions, that it is possible to conceive. There are subject to the British rule in Asia a hundred millions of people who do not profess the Christian faith. The Mahometans are a minority: but their importance is much more than proportioned to their number: for they are an united, a zealous, an ambitious, a warlike class.”

Brahminical idolatry is the worst of its religions: “The great majority of the population of India consists of idolaters, blindly attached to doctrines and rites which, considered merely with reference to the temporal interests of mankind, are in the highest degree pernicious. In no part of the world has a religion ever existed more unfavourable to the moral and intellectual health of our race. The Brahminical mythology is so absurd that it necessarily debases every mind which receives it as truth; and with this absurd mythology is bound up an absurd system of physics, an absurd geography, an absurd astronomy. Nor is this form of Paganism more favourable to art than to science. Through the whole Hindoo Pantheon you will look in vain for anything resembling those beautiful and majestic forms which stood in the shrines of ancient Greece. All is hideous, and grotesque, and ignoble. As this superstition is of all superstitions the most irrational, and of all superstitions the most inelegant, so is it of all superstitions the most immoral. Emblems of vice are objects of public worship. Acts of vice are acts of public worship. The courtesans are as much a part of the establishment of the temple, as much ministers of the god, as the priests. Crimes against life, crimes against property, are not only permitted but enjoined by this odious theology. But for our interference human victims would still be offered to the Ganges, and the widow would still be laid on the pile with the corpse of her husband, and burned alive by her own children. It is by the command and under the especial protection of one of the most powerful goddesses that the Thugs join themselves to the unsuspecting traveller, make friends with him, slip the noose round his neck, plunge their knives in his eyes, hide him in the earth, and divide his money and baggage. I have read many examinations of Thugs; and I particularly remember an altercation which took place between two of those wretches in the presence of an English officer. One Thug reproached the other for having been so irreligious as to spare the life of a traveller when the omens indicated that their patroness required a victim. “How could you let him go? How can you expect the goddess to protect us if you disobey her commands? That is one of your North country heresies.”

The great majority of the population of India consists of idolaters, blindly attached to doctrines and rites which, considered merely with reference to the temporal interests of mankind, are in the highest degree pernicious.

He has intervened to support Lingamism: “ So much for the first charge, the charge of disobedience. It is fully made out: but it is not the heaviest charge which I bring against Lord Ellenborough. I charge him with having done that which, even if it had not been, as it was, strictly forbidden by the Home authorities, it would still have been a high crime to do. He ought to have known, without any instructions from home, that it was his duty not to take part in disputes among the false religions of the East; that it was his duty, in his official character, to show no marked preference for any of those religions, and to offer no marked insult to any. But, Sir, he has paid unseemly homage to one of those religions; he has grossly insulted another; and he has selected as the object of his homage the very worst and most degrading of those religions, and as the object of his insults the best and purest of them. The homage was paid to Lingamism. The insult was offered to Mahometanism. Lingamism is not merely idolatry, but idolatry in its most pernicious form. The honourable gentleman the Secretary of the Board of Control seemed to think that he had achieved a great victory when he had made out that his lordship’s devotions had been paid, not to Vishnu, but to Siva. Sir, Vishnu is the preserving Deity of the Hindoo Mythology; Siva is the destroying Deity; and, as far as I have any preference for one of your Governor General’s gods over another, I confess that my own tastes would lead me to prefer the preserving to the destroying power. Yes, Sir; the temple of Somnauth was sacred to Siva; and the honourable gentleman cannot but know by what emblem Siva is represented, and with what rites he is adored. I will say no more. The Governor General, Sir, is in some degree protected by the very magnitude of his offence. I am ashamed to name those things to which he is not ashamed to pay public reverence. This god of destruction, whose images and whose worship it would be a violation of decency to describe, is selected as the object of homage.”

The duty of our Government is, as I said, to take no part in the disputes between Mahometans and idolaters. But, if our Government does take a part, there cannot be a doubt that Mahometanism is entitled to the preference.

He has offended and insulted the Mahometans: “As the object of insult is selected a religion which has borrowed much of its theology and much of its morality from Christianity, a religion which in the midst of Polytheism teaches the unity of God, and, in the midst of idolatry, strictly proscribes the worship of images. The duty of our Government is, as I said, to take no part in the disputes between Mahometans and idolaters. But, if our Government does take a part, there cannot be a doubt that Mahometanism is entitled to the preference. Lord Ellenborough is of a different opinion. He takes away the gates from a Mahometan mosque, and solemnly offers them as a gift to a Pagan temple. Morally, this is a crime. Politically, it is a blunder. Nobody who knows anything of the Mahometans of India can doubt that this affront to their faith will excite their fiercest indignation. Their susceptibility on such points is extreme. Some of the most serious disasters that have ever befallen us in India have been caused by that susceptibility. Remember what happened at Vellore in 1806, and more recently at Bangalore. The mutiny of Vellore was caused by a slight shown to the Mahometan turban; the mutiny of Bangalore, by disrespect said to have been shown to a Mahometan place of worship. If a Governor General had been induced by his zeal for Christianity to offer any affront to a mosque held in high veneration by Mussulmans, I should think that he had been guilty of indiscretion such as proved him to be unfit for his post. But to affront a mosque of peculiar dignity, not from zeal for Christianity, but for the sake of this loathsome god of destruction, is nothing short of madness.”

But to affront a mosque of peculiar dignity, not from zeal for Christianity, but for the sake of this loathsome god of destruction, is nothing short of madness.

Citation

[1] The Gates of Somnauth, by Thomas Babington Macaulay, a speech in the House of Commons, March 9, 1843 (franpritchett.com)